Tsunami History

As early as 426 B.C. the Greek historian Thucydides inquired in his book History of the Peloponnesian War about the causes of tsunami, and was the first to argue that ocean earthquakes must be the cause.The cause, in my opinion, of this phenomenon must be sought in the earthquake. At the point where its shock has been the most violent the sea is driven back, and suddenly recoiling with redoubled force, causes the inundation. Without an earthquake I do not see how such an accident could happen.The Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus (Res Gestae 26.10.15-19) described the typical sequence of a tsunami, including an incipient earthquake, the sudden retreat of the sea and a following gigantic wave, after the 365 A.D. tsunami devastated Alexandria.

While Japan may have the longest recorded history of tsunamis, the sheer destruction caused by the 2004 earthquake and tsunami event mark it as the most devastating of its kind in modern times, killing around 230,000 people. The Sumatran region is not unused to tsunamis either, with earthquakes of varying magnitudes regularly occurring off the coast of the island.

Generation mechanisms

The principal generation mechanism (or cause) of a tsunami is the displacement of a substantial volume of water or perturbation of the sea.This displacement of water is usually attributed to either earthquakes, landslides, volcanic eruptions,glacier calvings or more rarely by meteorites and nuclear tests. The waves formed in this way are then sustained by gravity. Tides do not play any part in the generation of tsunamis.Tsunami generated by seismicity

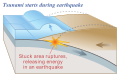

Tsunami can be generated when the sea floor abruptly deforms and vertically displaces the overlying water. Tectonic earthquakes are a particular kind of earthquake that are associated with the Earth's crustal deformation; when these earthquakes occur beneath the sea, the water above the deformed area is displaced from its equilibrium position. More specifically, a tsunami can be generated when thrust faults associated with convergent or destructive plate boundaries move abruptly, resulting in water displacement, owing to the vertical component of movement involved. Movement on normal faults will also cause displacement of the seabed, but the size of the largest of such events is normally too small to give rise to a significant tsunami.-

- Overriding plate bulges under strain, causing tectonic uplift.

- Plate slips, causing subsidence and releasing energy into water.

On April 1, 1946, a magnitude-7.8 (Richter Scale) earthquake occurred near the Aleutian Islands, Alaska. It generated a tsunami which inundated Hilo on the island of Hawai'i with a 14 metres (46 ft) high surge. The area where the earthquake occurred is where the Pacific Ocean floor is subducting (or being pushed downwards) under Alaska.

Examples of tsunami originating at locations away from convergent boundaries include Storegga about 8,000 years ago, Grand Banks 1929, Papua New Guinea 1998 (Tappin, 2001). The Grand Banks and Papua New Guinea tsunamis came from earthquakes which destabilized sediments, causing them to flow into the ocean and generate a tsunami. They dissipated before traveling transoceanic distances.

The cause of the Storegga sediment failure is unknown. Possibilities include an overloading of the sediments, an earthquake or a release of gas hydrates (methane etc.)

The 1960 Valdivia earthquake (Mw 9.5) (19:11 hrs UTC), 1964 Alaska earthquake (Mw 9.2), 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake (Mw 9.2) (00:58:53 UTC) and 2011 Tōhoku earthquake (Mw9.0) are recent examples of powerful megathrust earthquakes that generated tsunamis (known as teletsunamis) that can cross entire oceans. Smaller (Mw 4.2) earthquakes in Japan can trigger tsunamis (called local and regional tsunamis) that can only devastate nearby coasts, but can do so in only a few minutes.

Tsunami generated by landslides

In the 1950s, it was discovered that larger tsunamis than had previously been believed possible could be caused by giant landslides. These phenomena rapidly displace large water volumes, as energy from falling debris or expansion transfers to the water at a rate faster than the water can absorb. Their existence was confirmed in 1958, when a giant landslide in Lituya Bay, Alaska, caused the highest wave ever recorded, which had a height of 524 metres (over 1700 feet). The wave didn't travel far, as it struck land almost immediately. Two people fishing in the bay were killed, but another boat amazingly managed to ride the wave. Scientists named these waves megatsunami.Scientists discovered that extremely large landslides from volcanic island collapses can generate megatsunamis that can cross oceans.

Characteristics

Tsunamis cause damage by two mechanisms: the smashing force of a wall of water travelling at high speed, and the destructive power of a large volume of water draining off the land and carrying all with it, even if the wave did not look large.While everyday wind waves have a wavelength (from crest to crest) of about 100 metres (330 ft) and a height of roughly 2 metres (6.6 ft), a tsunami in the deep ocean has a wavelength of about 200 kilometres (120 mi). Such a wave travels at well over 800 kilometres per hour (500 mph), but owing to the enormous wavelength the wave oscillation at any given point takes 20 or 30 minutes to complete a cycle and has an amplitude of only about 1 metre (3.3 ft). This makes tsunamis difficult to detect over deep water. Ships rarely notice their passage.

As the tsunami approaches the coast and the waters become shallow, wave shoaling compresses the wave and its velocity slows below 80 kilometres per hour (50 mph). Its wavelength diminishes to less than 20 kilometres (12 mi) and its amplitude grows enormously. Since the wave still has the same very long period, the tsunami may take minutes to reach full height. Except for the very largest tsunamis, the approaching wave does not break, but rather appears like a fast-moving tidal bore. Open bays and coastlines adjacent to very deep water may shape the tsunami further into a step-like wave with a steep-breaking front.

When the tsunami's wave peak reaches the shore, the resulting temporary rise in sea level is termed run up. Run up is measured in metres above a reference sea level. A large tsunami may feature multiple waves arriving over a period of hours, with significant time between the wave crests. The first wave to reach the shore may not have the highest run up.

About 80% of tsunamis occur in the Pacific Ocean, but they are possible wherever there are large bodies of water, including lakes. They are caused by earthquakes, landslides, volcanic explosions glacier calvings, and bolides.

Source: Wikipedia

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar